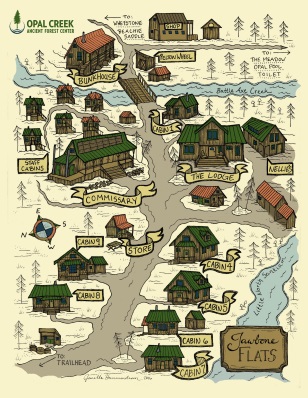

Jawbone Flats is the historic base of operations for Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center. Situated in the stunning temperate rainforest of the Western Cascades, it's surrounded by towering old growth trees and 5,000-foot peaks. Jawbone Flats has a long and rich history that begins long before the organization's inception.

Indigenous Peoples

At Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center, we live, work, and play on lands that were traditionally inhabited by the Santiam Molalla, who lived in watersheds just upriver of the Santiam Kalapuya. These two bands of Indian people have lived on the forested landscapes of the Western Cascades since time immemorial. Atlatl dart points, arrowheads and lithic scatter dating back thousands of years have been found within the Opal Creek watershed, including obsidian tools sourced to the Middle Sister area 50 miles to the southeast. Upper valleys and summits around the river confluence that would eventually come to be known as Jawbone Flats provided important summer foraging and hunting landscapes to these Indigenous bands, which also included pre-contact ridgeline and trans-montane trade routes connecting Tribes in all directions, such as the Whetstone Mountain Trail. As colonial pressure and white settlement grew, the Santiam bands of the Molalla and Kalapuya participated in the 1855 negotiation and signing of the Willamette Valley Treaty, whereby over 15 Indigenous groups ceded the majority of their aboriginal lands to the United States in exchange for a permanent reservation, annuities, supplies, educational instruction, vocational training, health services, and protection from violence by American settlers. Modern descendants of the ancestral Santiam Molalla and Santiam Kalapuya are citizens of the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde, as well as citizens of the United States. Many still spend summers in the forests of the Western Cascades, digging camas roots, picking huckleberries and visiting long-established family camping grounds.

of Indian people have lived on the forested landscapes of the Western Cascades since time immemorial. Atlatl dart points, arrowheads and lithic scatter dating back thousands of years have been found within the Opal Creek watershed, including obsidian tools sourced to the Middle Sister area 50 miles to the southeast. Upper valleys and summits around the river confluence that would eventually come to be known as Jawbone Flats provided important summer foraging and hunting landscapes to these Indigenous bands, which also included pre-contact ridgeline and trans-montane trade routes connecting Tribes in all directions, such as the Whetstone Mountain Trail. As colonial pressure and white settlement grew, the Santiam bands of the Molalla and Kalapuya participated in the 1855 negotiation and signing of the Willamette Valley Treaty, whereby over 15 Indigenous groups ceded the majority of their aboriginal lands to the United States in exchange for a permanent reservation, annuities, supplies, educational instruction, vocational training, health services, and protection from violence by American settlers. Modern descendants of the ancestral Santiam Molalla and Santiam Kalapuya are citizens of the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde, as well as citizens of the United States. Many still spend summers in the forests of the Western Cascades, digging camas roots, picking huckleberries and visiting long-established family camping grounds.

Miners

Circa 1859, miners explored the valley of the Little North Santiam River and discovered gold and other precious metals. Beginning in 1860, hundreds of mining claims were filed, and most associated documents spoke of the great promise of the area. The promise has never been actualized. Investments into road-building, hard-rock shafts and adits, and ore-processing and refining mill works have extended into millions of dollars, but the total production between 1880 and 1940 was reported as just over $25,000.

In 1893, the rugged and forested canyons containing these mining explorations were included in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve of Oregon. The initial set-aside as a reserve was to keep the land from being used by individuals, but after several years of protest over access and use (mostly over grazing rights of sheepherders), in 1897 the lands began to be managed more directly by the General Land Office of the United States, and by the Division of Forestry in the US Dept. of Interior. In 1905, forest reserves were transferred to the Division of Forestry in the US Dept. of Agriculture, which would thereafter be known as the US Forest Service.

In 1893, the rugged and forested canyons containing these mining explorations were included in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve of Oregon. The initial set-aside as a reserve was to keep the land from being used by individuals, but after several years of protest over access and use (mostly over grazing rights of sheepherders), in 1897 the lands began to be managed more directly by the General Land Office of the United States, and by the Division of Forestry in the US Dept. of Interior. In 1905, forest reserves were transferred to the Division of Forestry in the US Dept. of Agriculture, which would thereafter be known as the US Forest Service.

In 1908, the area of the original Cascade Range Forest Reserve was split into several subsidiary National Forests, including the Oregon National Forest, the Cascade National Forest, the Umpqua National Forest and the Crater National Forest. In 1911, the Santiam National Forest was created from parts of both the Oregon National Forest and the Cascade National Forest. Finally, in 1933, the Santiam National Forest and the Cascade National Forest were combined to form the Willamette National Forest.

Because the governing regulations for mining were the General Mining Law of 1872, and the mining claims along the Little North Santiam River were established prior to the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, James P. Hewitt and his Amalgamated Mining Co. were able to continue operations within the National Forest lands on their pre-existing claims, as well as file new claims. Hewitt began expanding the number and size of buildings at the Jawbone Flats mining camp in 1930, which was a mill site where lead, zinc, copper and silver were processed from ore. Some of the early mining roads and the Gold Creek Bridge were re-constructed in 1939 with CCC labor and funding from President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Amalgamated Mining’s lack of profitable operations impacted its viability, however, and by the time heavy snowfall damaged the Jawbone Flats buildings in the 1950s, large-scale operations had all but ceased.

In 1944, James Hewitt’s daughter Dolores married future Oregon governor Victor Atiyeh, introducing the Atiyeh family to the Opal Creek forests and landscape. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s Vic Atiyeh’s nephew George Atiyeh managed the Shiny Rock Mining Company which held Hewitt’s original claims and others. George Atiyeh lived part-time at Jawbone Flats with a tiny contingent of miners and their families, who did enough annual small-scale mining to keep the claims active. Shiny Rock Mining Company was only one of many private inholding landowners within the Little North Santiam River valley and within the Willamette National Forest whose rights derived from old mining claims.

Conservationists

In the 1970s and 1980s, plans by the US Forest Service to log forests in the Opal Creek watershed stirred up local activists who knew Opal Creek was one of the last large strongholds of a very special kind of ecosystem: low-elevation old growth forest of the Western Cascades.

George Atiyeh and other activists used private access provisions of the General Mining Law of 1872 to hold off the US Forest service while simultaneously promoting a congressional solution. In 1984, the Bull of the Woods Wilderness had been established in the adjacent watersheds to the north and east of Opal Creek, and it became evident that seeking a wilderness designation was a possible means to conserve the Opal Creek old-growth forest.

George Atiyeh and other activists used private access provisions of the General Mining Law of 1872 to hold off the US Forest service while simultaneously promoting a congressional solution. In 1984, the Bull of the Woods Wilderness had been established in the adjacent watersheds to the north and east of Opal Creek, and it became evident that seeking a wilderness designation was a possible means to conserve the Opal Creek old-growth forest.

By 1985, the Shiny Rock Mining Company had assembled 170 separate mining claims (including 7 patented claims) within the Opal Creek drainage totaling 151 acres, which included the associated Hewitt millsite claims located at Jawbone Flats.

In 1989, an Audubon documentary film titled Ancient Forests: Rage Over Trees featured the developing battle between conservation and logging interests over Opal Creek forests. The film was aired on Turner Broadcasting System (TBS), and hosted by actor Paul Newman. When word got out about the film’s content, the logging industry was able to convince TBS’s main corporate sponsors to withdraw from their commercial advertising time slots. Nonetheless, owner Ted Turner broadcast the film in primetime, with promotions for future showings replacing the commercials. TBS ended up showing the film multiple times, and more than anything else, this film raised the Opal Creek ancient forest controversy from a local Oregon issue to a national one.

The Friends of Opal Creek non-profit corporation was established in 1989 by George Atiyeh and friends in an effort to secure permanent protection of the watershed by increasing public awareness of the natural and cultural resources, scenic beauty, plant and animal diversity, and ecological complexity of this extraordinary area. In 1992, the last small-scale mining at Opal Creek ceased and the Shiny Rock Mining Company gave Friends of Opal Creek a land gift valued at $12.6 million. This gift encompassed Shiny Rock’s entire 151 acres of mineral claims, including 15 acres of Jawbone Flats and important stands of old-growth forest.

Controversy over the US Forest Service’s and other federal agencies’ old-growth logging policies across the entire Pacific Northwest continued, and in 1993, the Clinton administration held a series of studies and hearings, ultimately adopting the Northwest Forest Plan in 1994. This plan directed federal agencies to identify management alternatives that would meet the requirements of many ecological conservation laws, and would ultimately be “scientifically sound, ecologically credible, and legally responsible” and would produce a predictable and sustainable supply of timber.

hearings, ultimately adopting the Northwest Forest Plan in 1994. This plan directed federal agencies to identify management alternatives that would meet the requirements of many ecological conservation laws, and would ultimately be “scientifically sound, ecologically credible, and legally responsible” and would produce a predictable and sustainable supply of timber.

Even with the risk of cutting Opal Creek’s old-growth trees reduced, legislative efforts to conserve Opal Creek continued. Retiring Oregon Senator Mark Hatfield pushed forward a bill, signed into law in October 1996, establishing the 20,827-acre Opal Creek Wilderness, the 13,538-acre Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area and a 3,066-acre Wild and Scenic River designation for Elkhorn Creek. Except for the unique 15-acre private inholding of Jawbone Flats, the Opal Creek Act required all other privately-owned lands be returned to public ownership.

Educators

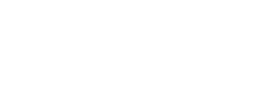

After the passage of the public law, the historic mining town of Jawbone Flats was closely bordered on the north by the Opal Creek Wilderness, and surrounded on the south, east, and west by the Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area. Jawbone Flats itself was transformed into a site for learning about old-growth forest ecology. In 2005, the Friends of Opal Creek, operating out of Jawbone Flats, changed our name to the Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center.

After the passage of the public law, the historic mining town of Jawbone Flats was closely bordered on the north by the Opal Creek Wilderness, and surrounded on the south, east, and west by the Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area. Jawbone Flats itself was transformed into a site for learning about old-growth forest ecology. In 2005, the Friends of Opal Creek, operating out of Jawbone Flats, changed our name to the Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center.

Between 1996 and 2020, Jawbone Flats bustled with school children each spring and fall, who were busy exploring and enjoying one of the most unique and remote Outdoor School experiences available in Oregon. During summers, our Opal Creek Expeditions guided beginning backpackers deep into the surrounding rugged wilderness areas for weeklong trips. We also ran a small rental program in the old historic mining cabins, offering a unique backcountry lodging experience deep within the lush old growth forest.

By the year 2000, the Little North Santiam River canyon and Opal Creek had become an important recreation and tourism destination, and a quintessential Oregon experience: “As Oregon as it gets”. Trails through the old-growth forest were full of awed hikers, and in summer, the clear pools of cold water were beloved by swimmers. The region typically drew over 20,000 visitors each year, including many who stopped at Jawbone Flats to look at the mining artifacts, or ask questions about the ecology of the ancient forest.

The Next Chapter

In September of 2020, the catastrophic Beachie Creek Fire burned nearly all of the historic cabins and buildings of Jawbone Flats. Cabin 4 (a cabin rebuilt in 2000), our new outdoor classroom, and our water treatment plant are the only buildings that remain standing today.

Forest fires in old-growth forests are rarely totally devastating. The forests around Jawbone Flats have previously survived two forest fires, estimated to have occurred around 1550 and 1835. Within the Opal Creek and Battle Ax Creek watersheds, many big trees survived, particularly those located in cool, wet places along the area’s streams. Upper slopes burned hot, however, and most of the forests in the canyon of the Little North Santiam River fell victim to the inferno.

Nonetheless, Jawbone Flats and the surrounding forests have been occupied by humans for thousands of years. The site at the confluence of those creeks has persisted through forest fires, debris flows, and other natural landscape formation processes. For well over 100 years, the scenic canyons surrounding the Little North Santiam River were subject to the destructive and extractive pressures of mining, but conversely the region is also the site of one of the most highly visible forest conservation success stories in the United States.

Jawbone Flats survived the Beachie Creek Fire of 2020. The Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center is entering a new chapter. Post-fire, our organization’s efforts turn to creating a new site and facility plan at Jawbone Flats that is resilient, in harmony with the land, and will support the amazing education programs we will be able to offer. We intend to focus on the complex and multicultural human history of this landscape, and to use it as leadership curriculum for challenging human decisions over resource use, resiliency, and the duality of extraction and conservation. Our organizational mission is to …provide transformative wilderness experiences that grow a community of environmental advocates. We look ahead to returning to Jawbone Flats and putting our mission into action for the next generation, and the many following.

Join us as we continue forward!